BITERs a story from 21st Century Dead

Posted on July 20, 2012 by Flames

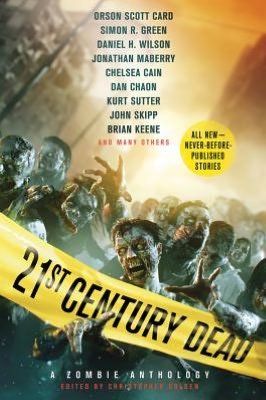

The Stoker-award winning editor of the acclaimed, eclectic anthology The New Dead returns with 21st Century Dead, and an all-new lineup of authors from all corners of the fiction world, shining a dark light on our fascination with tales of death and resurrection… with ZOMBIES!

The stellar stories in this volume includes a tale set in the world of Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse, the first published fiction by Sons of Anarchy creator Kurt Sutter, and a tale of love, family, and resurrection from the legendary Orson Scott Card. This new volume also includes stories also from other award-winning and New York Times bestselling authors, such as: Simon R. Green, Chelsea Cain, Jonathan Maberry, Duane Swiercyznski, Caitlin Kittredge, Brian Keene, Amber Benson, John Skipp, S. G. Browne, Thomas E. Sniegoski, Hollywood screenwriter Stephen Susco, National Book Award nominee Dan Chaon, and more!

Flames Rising is pleased to present an excerpt from this collection by editor Christopher Golden.

BITERS by Mark Morris

THE GUARD ON THE GATE stared at Mrs. Keppler’s pass for a long time. He stared at it for so long, his face stern beneath his peaked cap, that Fleur began to get nervous. When the guard went back into his little hut, Fleur felt sure it was to call for reinforcements. She knew she’d done nothing wrong, and she was pretty sure that neither her friends nor Mrs. Keppler had done anything wrong, either, but the sense of guilt and crawling dread persisted just the same.

THE GUARD ON THE GATE stared at Mrs. Keppler’s pass for a long time. He stared at it for so long, his face stern beneath his peaked cap, that Fleur began to get nervous. When the guard went back into his little hut, Fleur felt sure it was to call for reinforcements. She knew she’d done nothing wrong, and she was pretty sure that neither her friends nor Mrs. Keppler had done anything wrong, either, but the sense of guilt and crawling dread persisted just the same.

Maybe it was the research facility that gave her these feelings. It was like a prison, all high steel fences and barbed wire and clanging gates. In that sense, it was like a smaller version of the compound in which they all lived. But the difference with the compound was that you couldn’t see the fences, not on a day-to-day basis anyway. And the guard uniforms were different here, gray and more formal than the faded brown combat fatigues that her brother Elliott and the rest of the perimeter security team wore. She saw the guard in the gray uniform speaking into a telephone and casting glances in their direction. Finally he put the phone down and marched stiffly across to the open door of the yellow school bus, where Mrs. Keppler was patiently waiting. Fleur was so relieved to see a smile break across the guard’s face that her breath emerged in a gasp.

“That’s all fine, madam,” he said. “You have clearance to proceed.”

Mrs. Keppler thanked him and the doors of the school bus concertinaed shut. The huge gates creaked slowly inward and Mr. Medcalf, their driver, drove through the widening gap.

Inside the facility, which looked to Fleur like nothing more than a mass of giant concrete building blocks stuck haphazardly together, more gray-uniformed men were pointing and waving their arms. Following their directions, Mr. Medcalf drove around to a car park at the back, where a squat, bald man whose brown suit matched the color of his bristling mustache directed them with fussy hand movements into a designated space.

“Welcome to the Moorbank Research Facility,” the man said when they had disembarked. “I understand you’re here to participate in the Infant Care Program?”

Mrs. Keppler, a tiny, owlish woman, who to Fleur and her friends seemed ageless, said, “Yes, that’s right.”

“Excellent.” Raising his voice slightly to address the class, the man said, “My name is Mr. Letts. I’m the assigned facilitator for your visit here today. I’ll be escorting you to the Crèche, explaining the procedure, and answering any questions you may have. Can I ask that you stick close together at all times and follow my instructions? We don’t want anyone getting lost now, do we?”

He bared his small white teeth in a grin, which instantly tightened to an exasperated grimace when a hand shot up.

“Yes, Joseph,” Mrs. Keppler said.

“Sir, miss, I was wondering, are the betweeners allowed to walk around inside?”

A few of his classmates sniggered at the babyish phrase. In her sweet and patient voice, Mrs. Keppler said, “Of course not, Joseph. We won’t be in any danger. Isn’t that right, Mr. Letts?”

“Oh, absolutely,” Mr. Letts agreed. “Security is paramount here at Moorbank.”

He led them across the car park, toward a pair of large glass doors beneath a curved metal awning. Next to the doors, inset into a recess in the wall, was a dark glass panel. The pressure of Mr. Letts’s hand on the panel activated a crisscrossing network of glowing red lasers, which drew murmurs of appreciation from the children. After the lasers had scanned Mr. Letts’s handprint, a series of clunks announced that the locks sealing the doors had disengaged, allowing their guide to lead them inside.

“It smells funny,” whispered Millie to Fleur, before clenching her teeth as her words echoed around the high-ceilinged lobby.

Her voice clearly didn’t carry as far as the girls had thought, because the only person who answered was Alistair Knott, who stooped to push his freckled face between the girls’ heads to murmur, “That’s the chemicals they use to keep the biters fresh.”

Millie pulled an “eeew” face and shuddered violently enough to rattle her beaded dreadlocks, but Fleur just rolled her eyes. As Mr. Letts led them along a series of featureless corridors and up numerous flights of stairs, Fleur recalled Mrs. Keppler telling them in their history lessons that although people had started turning into what Alistair had called “biters” before Fleur and her classmates were born, it wasn’t really all that long ago—only thirty or forty years. It was long enough, Mrs. Keppler had said, for the world to have changed from the way it had been at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and for the living to have become sufficiently organized that their lives weren’t a daily battle for survival. However, it was not really long enough for the older generations, who remembered how things used to be, to have fully come to terms with the situation, or for scientists to have found a cure for the R1 virus.

The R in R1 stood for Reanimation. Mrs. Keppler had told them that, too, though Fleur, like most kids, had known that since she could remember. It was a word she heard almost daily. It was what politicians and newsreaders called those with the virus: the Reanimated. Most people, like Elliott and Fleur’s mum, Jacqui, just called them R1s, though sometimes Elliott called them “reamers.” Jacqui didn’t like him using that word, though; she said it was “derogatory,” which Fleur thought meant that it was kind of a swearword, though she wasn’t sure why. Most little kids called the R1s “betweeners” because they were neither one thing nor the other. And there were other words for them, too, slang words like biters and decoms and loads of others.

What people never seemed to say, though, not directly anyway, was that the R1s were dead. It was like it was a taboo subject. It was like admitting something that was dark and forbidden. On TV, R1s were always described as “sufferers” or “victims” or “the infected.” Fleur knew that scientists had been searching for a cure for the R1 virus for years, and she thought the reason why no one ever actually said the R1s were dead was that you couldn’t cure death, and therefore that would mean the scientists had been wasting their time. When Fleur had asked Jacqui what the Reanimated were reanimated from, her mum had mumbled something about it being a “gray area.” And when Fleur had pushed her to explain further, Jacqui had gotten angry and said she didn’t want to talk about it.

The facility was such a maze of corridors, staircases, and numbered doors that the novelty of being inside it quickly paled. Fleur tried to imagine what might lie behind the doors. Offices? Laboratories? Cells for the inmates? If so, they must be empty or soundproofed, because, despite walking for what seemed miles, she and her classmates did not encounter another soul, living or otherwise, on their journey. Plus, they heard nothing but their own clomping feet and Mr. Letts’s occasional barked orders to stay together.

When their guide finally turned and held up a hand, Fleur initially thought it was to reprimand those children who had begun to moan about their aching feet. Then Mr. Letts turned to a keypad and tapped in a code, whereupon the door beside it unsealed with a magnified wheeze. He marched inside without explanation, leaving Mrs. Keppler to usher the children after him.

Entering shoulder to shoulder with Millie, Fleur found herself in a white oblong room twice as big as her sitting room at home. Despite its size, however, it was spartan, but for a desk, chair, and computer tucked into an alcove in the left-hand wall. The most notable thing about the room was that almost the entire wall behind Mr. Letts, who had turned to face the children filing through the door, was composed of black glass. It reminded Fleur so much of a cinema screen that she half expected Mr. Letts to tell them to sit down in cross-legged rows to watch a film about the history and function of the facility.

He didn’t, however. He simply stood, hands clasped in front of him, until they were all quiet. Then he said, “This is the observation and monitoring room for the Crèche here at Moorlands. Behind me is the Crèche itself, which I’m sure you are all eager to see. However, before I reveal it, I need to prepare you as much as I’m able for what you’re about to experience. I also want to talk for a few minutes about the Infant Care Program in general. Before I start, can I ask how many of you have seen photographs or news footage of the Reanimated?”

Almost all the children raised their hands.

“And how many of you have seen the Reanimated in the flesh?”

All but two of the hands went down.

Mr. Letts fixed Ray Downey, who still had his hand up, with a penetrating stare. “Would you care to tell us about your experience?”

Now that he had been put on the spot, Ray’s smug expression slipped into one of nervousness. As if justifying himself, he said, “I was with my friend Jim Brewster. We were on our bikes one day and we heard all this shouting ’round the back of Hampson’s store, so we went down to take a look. The biter was this old guy who must have gotten sick somewhere nearby and hadn’t been reported in time. Mr. Hampson and some other men were holding him off with poles. Then the cops … er, the police came and they caught the biter in a net and took him away in a van.” Almost reluctantly he added, “It was pretty cool.”

“Cool,” repeated Mr. Letts tersely. “Is that what you really thought?”

Ray Downey shrugged.

Pursing his lips disapprovingly, Mr. Letts turned to John Caine, the other boy with his hand up. “What about you?”

John’s blond fringe twitched as he blinked it out of his eyes. His voice was so low and muffled that it sounded as if his throat were trying to hold it back. “My dad took me to see the perimeter when I was six. We didn’t go very close. We parked on a hill looking down on it. When we were there we saw an R1 come up to the fence. A woman.”

“And how did that make you feel?”

John frowned in embarrassment or resentment. “Scared,” he admitted.

“Why?”

“Because she made a horrible noise. And her skin was all sort of … blue and purple.” As if the memory had enlivened him, the rest of his words emerged in a rush that threatened to descend into incoherence. “There was this look on her face. Blank, but like something had taken her over, as if she was a person but not really a person, as if she had turned into something awful.…” He ended with a coughing gasp, as if he’d run out of breath, and then in the same low, muffled voice with which he’d started his account he added, “It gave me nightmares.”

Mr. Letts nodded as if in approval. “Thank you. That is closer to the response I was looking for.” Clasping his hands again, he said, “The point is that a firsthand encounter with an R1 is far more debilitating and disturbing than any amount of photographs or news footage can ever convey. The reason for this is that the Reanimated don’t give off the subtle human signals we’re used to, and which we subconsciously pick up on all the time; and so, denied of that input, and coupled with their alarming appearance, our minds automatically recoil from them. It finds them repugnant, it finds them wrong, and therefore something to be avoided.”

He paused, allowing his words to sink in. Then he said, “That, I’m afraid, is something that you’re all going to have to accept and put aside in this instance. As I’m sure you have been informed, the Infant Care Program has been designed and formulated with a number of objectives in mind. First, it is to give young people like yourselves prolonged exposure to R1 sufferers—but exposure which, if you behave responsibly, will not result in the slightest risk or injury to either yourselves or those around you.

“Now, some of you may be wondering why exposure to the Reanimated is considered such a valid and valuable exercise. The simple answer is that it will both enable you to understand and come to terms with those afflicted by the virus, and also hopefully allay some of the fears and prejudices you perhaps have about them. R1 is part of our world now, and despite ongoing research it is unlikely to disappear in any of our immediate futures. The more understanding and acceptance we therefore have of its effects and of those afflicted by it, the better it will be for all concerned in the long term. After all, it is likely that some of you will be working with, or in close proximity to, R1 sufferers once you leave school and venture into the world of employment. It is therefore best to be prepared—and the Infant Care Program is an invaluable step toward that state of preparation.”

Warming to his subject, he continued. “A further reason why the program itself has been implemented is to give young people a chance to temporarily assume what is in effect a considerable amount of personal responsibility. This may seem daunting, even frightening, at first, but we in the program hope that ultimately you will come to look upon this next week as both a challenge and an opportunity to show just how mature and resourceful you can be. Before I talk about the specifics of your assignments, let me dispel some of the rumors about R1.”

He raised a finger, as if about to accuse them of starting the rumors themselves. And then, as forcefully as if resuming an argument, he said, “Yes, R1 is a virus, but it could only be contracted by living beings such as yourselves if your blood and/or other bodily fluids were to become mingled with that of an R1 sufferer. R1 is not—I repeat not—an airborne virus. Neither can it be contracted simply by touching the flesh of a sufferer—however, we will issue you a plentiful supply of disposable gloves as an extra precaution against physical contact.

“In the unlikely event that you should get scratched or bitten by your assigned R1 infant during the course of the program, the important thing to remember is, firstly, not to panic, and secondly, to seek immediate medical attention. Although we are still some way from finding a cure for the virus, we have discovered a vaccine that can eradicate R1 cells in the early stages of infection. Evidence has shown that patients treated with this vaccine within the first ninety minutes of infectious contact have a 98.7 percent recovery rate. However, there is no need whatsoever for you to become involved in any situation where there is even the remotest risk of infection. The R1 infant assigned to you should remain muzzled at all times, and as long as you adhere to the necessary precautions you will be fine.”

Alistair Knott raised a hand. Mr. Letts frowned. “Yes?”

“What about feeding time?” Alistair asked. “Won’t we have to take the muzzles off then?”

“Not at all,” Mr. Letts replied curtly. “We will issue you more than enough disposable feeding tubes, which you attach to the front of the muzzle. I will demonstrate how in a few minutes.”

As if Alistair’s question had emboldened the rest of the class, Millie now raised her hand. “What about the smell?” she said. “My mum says she doesn’t want an R1 in the house because they stink.”

Mr. Letts looked momentarily outraged, but a huff of exasperation downgraded the expression into a scowl. Acidly he said, “The facility’s inmates do not smell. Like all R1 sufferers, it’s true that their bodies have succumbed to a limited amount of physical corruption—a process which is subsequently arrested by what we call the ‘R1 barrier,’ which incidentally we still do not fully understand—but all of our test subjects have been treated with a combination of chemicals which negates the more unpleasant effects of bodily decomposition.” He glanced at Mrs. Keppler. “Well, if there are no more questions, I think it’s time for you to become acquainted with your charges.”

For the first time Fleur felt jittery with nerves as the class lined up, each to be presented with a metal tag bearing a four-digit number. When that was done, Mr. Letts crossed unhurriedly to a narrow door tucked between the edge of the glass screen and the adjoining wall and tapped out a code on a keypad. The effect of his action, as he stepped back, was twofold. The lights flickered on in the Crèche, transforming the black screen into a viewing window, and the door unlocked with a series of clicks.

As she shuffled forward behind a dozen of her classmates, Fleur glanced almost unwillingly at the room beyond the glass. She was just in time to see rows of evenly spaced incubators made of opaque plastic the color of sour milk before she was through the door and among them.

The first thing that struck her about the Crèche was its stillness. The incubators were so silent that they might have been occupied by dead meat, or nothing at all. The stillness seemed to reach out and stifle the combined sound of almost thirty thirteen-year-olds—the rustle of clothing, the squeak of rubber soles on vinyl flooring, the soft rasp of respiration that was trying not to escalate beyond nervousness. When Mr. Letts, who had slipped into the room at the back of the group, spoke, it made them all jump.

“Some of you may be experiencing a sense of disquiet, perhaps even anxiety or distress, about now. Am I right?”

As if on cue, one of the girls—Fleur thought it might have been Lottie Travis—failed to curtail a sob. Around her, she became aware of heads nodding slowly, and then of her own joining in.

“That’s a perfectly natural reaction,” Mr. Letts said in an almost kindly voice. “Living babies are a bundle of instincts. As human beings we’re used to them moving almost constantly, even in repose—but the R1 infants, as you will see, are a different case entirely. Their only instinct is to feed, but they seem to know—or at least their bodies do—that there is little point transferring energy and resources into limbs that do not respond in an efficient manner. Therefore, they remain motionless as they wait to be fed. Having lived almost all their short lives in the facility, they have become creatures of habit. They feed three times a day and they expel waste products once a day. The advantage of this for you is that as long as you administer to these routine requirements, you will find the R1 infants simple to maintain. If, however, you deny them their sustenance for any length of time then they will do what normal infants do. Can you guess what that is?”

Fleur put up her hand. “Cry?”

“Exactly,” replied Mr. Letts. “Though it is a cry you will never have heard before, and almost certainly will never want to hear again.”

Behind her, Fleur heard another sob tear itself loose from Lottie. There was a prolonged shuffle and bump as Mrs. Keppler led the girl through the crowd and out of the room, and then Mr. Letts said, “Time to match you up, I think.”

Gesturing toward the incubators, he told them to search for the ones that matched the numbers on their tags. Fleur looked at hers as her classmates shifted around her like restless cattle. After a few seconds, several of her peers—Ray Downey, Alistair Knott, Tina Payne—broke away from the huddled group and began to move tentatively among the rows of tiny plastic boxes.

“What’s your number?” Millie asked almost fearfully, as if one of the tags might prove the equivalent of a short straw.

“It’s 4206,” Fleur replied.

“Mine’s 9733. Let’s look together, shall we?”

The numbers on the incubators seemed random, as if this were a treasure hunt or a puzzle, but Fleur supposed they must adhere to some system somewhere. Like Millie, she tried to focus on the numbers stamped on the ends of the plastic boxes rather than on their contents, which remained nothing but darkish blurs on the periphery of her vision. It took her several minutes, but at last she spotted the number that matched the one on her tag.

“It’s here,” she said, suddenly breathless.

“What have you got?” asked Millie. “A girl or a boy?”

“I daren’t look,” Fleur replied.

“I’ll look for you then, shall I?” Millie moved up beside her. After a few seconds, she quietly said, “It’s a boy.”

Fleur felt as though she were having to override a physical restraint in order to raise her head. She managed it at last, blinking to focus her gaze. The baby in the incubator was lying on its back with its arms upraised in a crucifix position. It looked not dead but as if it was pretending to be, which was somehow worse. Its eyes were dark glints in its mottled, bluish face, and its chest, which should have been rising and falling, was as still as a lump of clay and not dissimilar in texture.

“He’s cute,” Millie said, not at all convincingly. “What are you going to call him?”

Fleur’s thoughts felt as heavy as wet cement. She blurted out the first and only thing that came to mind.

“Andrew,” she said. “After my dad.”

* * *

“So this is it, is it?”

Elliott peered into the portable crib, which Fleur had put on the kitchen table. As always, he looked tired and grubby after a long shift spent patrolling the perimeter, his hair peppered with the dust that kicked up from the scrubland. He was twenty, lean and muscular, often difficult to predict emotionally. Sometimes he was broody, uncommunicative; at other times he was easygoing, quick to smile. Fleur loved her brother, but she couldn’t say that she fully understood his quicksilver personality. Needless to say, most of her friends found him mysterious, and so had a massive crush on him.

“He’s a he, not an it,” she said.

Elliott snorted. “Has Mum seen it?”

“Not yet. She’s at Aunty Valerie’s.”

“Course,” said Elliott, raising his eyebrows. “It’s Friday. I lose track in my job.” He opened the fridge, took out a bottle of soda, and opened it with a crack and a hiss. Dropping his weight into a wooden chair with a groan, he took a swig, then gave her a shrewd, sidelong look. “She won’t like having it in the house, you know. She hates those things.”

Fleur felt irritably defensive. “He can’t help how he is.”

Elliott shrugged. “Even so.”

As Fleur prepared the baby’s feed, the silence stretched between them. It was a silence redolent of bad memories and unspoken grief. The reason why Elliott was a perimeter guard was that their father had been one before him. Seven years ago, when Fleur was six and Elliott thirteen, Andy McMillan had been on patrol when a section of faulty fencing in his quadrant had collapsed, allowing a group of at least two dozen R1s to swarm into the compound. In the ensuing melee, Andy had suffered multiple bites—so many that the virus had taken hold quickly. Jacqui was the only one who had seen her husband in the hospital, raging and inhuman. And it was she, alone and traumatized, who had had to make the terrible decision that faced all R1 sufferers’ next of kin—to allow their loved ones to live on in a contained, controlled environment or to give the order to bring their suffering to a swift and humane end.

Fleur had been too young to fully appreciate Jacqui’s anguish over the decision, but Elliott’s reaction and the subsequent screeching arguments between Fleur’s mother and brother were scarred into her memory. Elliott had accused Jacqui of murdering their father. Jacqui had retaliated by saying that she had only been carrying out Andy’s wishes, that he had made it abundantly clear that if the worst ever happened, the last thing he would want would be for his family to see him reduced to the state of a slavering, mindless animal.

Eventually, of course, the raw wounds had closed up and the arguments had subsided. But they had never properly healed. There had been so much venom released during the endless round of accusations and counteraccusations, so much anger and hatred and hurt expelled and absorbed by both sides, that there would always be a tenderness there, a weak spot. Jacqui and Elliott loved each other, relied on each other, looked out for each other—but there still existed an underlying tension between them, a sense that if, for whatever reason, circumstances should ever force the wound to reopen, then all the old venom and more besides would come gushing out anew.

It was Elliott who eventually broke the silence. “That stuff smells disgusting.”

Fleur couldn’t disagree. She had emptied one of the sachets of powdered meal, which they had each been given before leaving the facility, into a bowl and was now adding hot water, as instructed. The stench that rose from the reddish paste was like the most rancid dog food imaginable. Holding her breath and screwing up her eyes, she nodded at a silvery rucksack emblazoned with the Moorlands logo, which was leaning against a table leg. “Get a feeding tube out of the pack, will you?”

Elliott stretched out a leg, hooked the pack with his foot, and pulled it to him. He rummaged through its contents and extracted a short length of corrugated tubing with a metal screw attachment at one end and a funnel at the other.

“I’m guessing you mean one of these,” he said, handing it to her.

She took it from him. “Thanks.”

He watched as she screwed the tube into a circular aperture at the front of the visorlike muzzle that was fastened securely around the lower half of the baby’s face.

“Fucking grotesque,” Elliott said with a bleak laugh. “Now it looks like an elephant fetus.”

Ignoring her brother, Fleur mixed cold water into the thick, foul-smelling gruel and then began to spoon it into the funnellike end of the feeding tube. After a moment the baby’s black eyes widened, its limbs began to twitch and squirm, and it began to eat with a muffled, wet, gnashing sound.

“Oh, that is totally gross,” Elliott said almost delightedly, rocking back in his chair.

Fleur shot him a disapproving look. “He needs to eat, Elliott.”

Elliott sat forward again abruptly, his eyes narrowing. “Why does he? I mean, why does it?”

Because it’s a school project,” Fleur said. “I have to look after him. Do you want me to fail for being a bad mother?”

Elliott shrugged. “Who’s going to know?”

Fleur pointed at a thin metal bracelet around the baby’s right wrist. “That monitors his physical state—his metabolism and stuff. They’d know if I didn’t look after him properly.”

Elliott peered at the bracelet. “I could probably fix that.”

“Don’t you dare!” said Fleur. “I want to do this properly.”

“Why?”

“I just do, that’s all.”

Elliott pulled a face. “Well, I think it’s sick. Looking after those things, keeping them alive…”

“They’re test subjects,” said Fleur. “Without live subjects we’d never find a cure for the R1 virus.”

“That’s what you’re doing now, is it?” taunted Elliott. “Vital medical research?”

Before Fleur could reply, there was the rattle of a key in the lock and the front door opened, admitting a brief roar of traffic noise.

Fleur tensed as her mother’s footsteps approached the kitchen. She’d wanted to get the first feed over and done with before Jacqui arrived home. As it was, her mother appeared in the kitchen doorway with her face screwed into an expression of repugnance.

“What’s that awful smell?” she said.

“It’s the baby’s feed,” said Fleur nervously. “Sorry, Mum. It does pong a bit.”

Jacqui put down her bags and sloughed off her threadbare coat as she walked across the room. She’d become thinner over the last few years, though not in a healthy way. She looked haggard and pale, her green eyes too large for her once elfin face, her almost-black hair tied back in a lifeless ponytail. Fleur felt her guts squirm as her mother examined the feeding infant, the repugnance on her face hardening into something more deep-rooted.

“How was Aunt Valerie?” Fleur asked, to break the silence.

“Same as always.” With barely a pause, Jacqui asked, “Where are you going to keep it?”

“In my room,” Fleur said.

“It’ll stink the place out.”

“It doesn’t smell. Only its food does. It’ll be finished in a minute.” She avoided Elliott’s eye as she spoke, aware that she, too, was now referring to the baby not as “he” but “it”—compromising her principles to avoid conflict.

To her surprise, her mum said, “Poor creature.”

Elliott made a noncommittal sound that could have been an acknowledgment of her comment or a rebuttal of it.

“I thought you hated the R1s,” Fleur said tentatively.

“I hate the virus,” Jacqui said. “And when people get infected, the virus is all they become.” She nodded at the baby. “It doesn’t mean I don’t grieve for the people the virus wipes out, the ones who once occupied the flesh—or in this case the one who never even got a chance to become a person.”

“You don’t think the real person is still in there somewhere then?” said Fleur. “And that if they find a cure those people will come back?”

All sorts of emotions chased themselves across Jacqui’s face. “I want to believe,” she said eventually. “But I don’t know if I can.”

* * *

“Ricky Jackson’s dad took his back. Said he and Ricky’s mum couldn’t stand having it in the house. So did Lottie Travis’s mum—she said it was giving Lottie nightmares. But did you hear about Tina Payne?” Millie’s brown eyes were wide.

Fleur shook her head.

“Get this,” Millie said, and lowered her voice to a dramatic murmur. “Her dad came home drunk, and the baby was crying ’cause Tina wasn’t feeding it properly. So he took it outside and dumped it headfirst in the bin and buried it under some rubbish and didn’t tell anyone. It was there two days before Tina went out and heard it crying.”

“That’s awful,” said Fleur. “Was it all right?”

Millie’s shrug sent her dreadlocks swaying and clinking. “S’pose. They don’t die, do they, even if you don’t feed them? You have to cut off their heads or burn them to kill them.”

Fleur tried to imagine being upside down in a bin full of stinking rubbish for two days. The thought of it made her feel sick. “Do they feel pain or distress, do you think?”

Millie pulled a face. “Don’t think so. Don’t think they feel anything really.”

“Must be awful,” said Fleur.

Millie nodded. “Yeah, I’d rather be dead than…” Then she realized what she was saying and clenched her teeth in apology. “Hey, sorry, I didn’t mean…”

Fleur waved a hand as though wafting a fly. “It’s okay. So how did you find out all this stuff anyway?”

Millie dipped her hand into the pocket of her shorts and extracted a wafer-thin rectangle with a burnished steel finish. “Smartfone 4.5,” she said. “Gossip Central. You should get one. Then we could talk all the time.”

“I wish,” said Fleur, trying not to look envious. “But we can’t afford it. We’ve only got Elliott’s wage coming in. Mum’s got a 2.5, but she doesn’t let me use it.”

“Bummer,” said Millie, then her eyes brightened. “Hey, I might be getting a new 5.1 for Christmas. If I do, you can have this one.”

“Thanks,” said Fleur, but she knew that even with the best network deal she could find, she would still never be able to afford to actually use the damn thing.

That was the only drawback about coming to Millie’s—sometimes her best friend forgot, or simply didn’t realize, how tight money was for Fleur and her family. That was why she hadn’t seen Millie for the whole of the half-term holiday—she couldn’t afford the bus fare and it was too far to walk. Ordinarily Fleur might have cycled around on her rickety old bone shaker, but with Andrew to look after she hadn’t been able to. So she had been stuck at home all week with nothing to do except feed and change the baby, read books, and do household chores for Mum.

Now, however, it was Friday, which Mum always spent with Dad’s sister, Aunt Valerie. Jacqui passed Millie’s house on the way to Valerie’s, so Fleur had persuaded Mum to drop her off en route and pick her up again on the way home.

The house Millie lived in was big, with apple trees in the front garden and a huge backyard with a swimming pool. Beyond the yard was a meadow, and beyond that was woodland. If you walked straight through the woods for about four hours, Millie’s fifteen-year-old brother, Will, had told them, you would come to the perimeter. He had been there with his friends several times and said it was “jazz” and that they should do it sometime. However, the girls preferred to stay close to civilization—to the pool and the computer and Millie’s mum’s homemade peanut cookies.

Today had been the warmest day of the holiday. The girls had been for a swim and were now sitting on the wooden seat that encircled the largest of the ancient fruit trees in the front garden. Their backs were resting against gnarled bark that had been worn smooth by the pressure of many such backs over the years. Sunlight winking through the leaves overhead formed a moving pattern of light and dark on their bare legs.

“Can’t wait to give the stupid thing back,” Millie said. “Only three days to go now.” She waved her clenched fists in the air and made a muted cheering sound.

Fleur glanced at Andrew, lying like a dead weight in his portable crib a few meters away. He seemed unaffected by the sunlight shining directly onto his tiny, mottled, blue-gray body.

“It hasn’t been so bad,” Fleur said. “In fact, it’s been quite easy.”

“Yeah, but I dread waiting for mine to shit every day,” said Millie. “It stinks like … rotting fish or something. Doesn’t it make you gag?”

“I’ve gotten used to it,” Fleur said. “I hold my breath.”

“But it’s the look of it,” said Millie, pulling a face. “It’s green. And slimy.”

Fleur grinned and was about to reply when a howl of pain from behind the house sliced through the drowsy afternoon air. This was followed by several people shouting at once, their voices shrill with panic.

“That’s Will,” Millie said, jumping to her feet.

She ran toward the path that led around the side of the house. Fleur glanced at Andrew, lying motionless in his crib, decided he’d be fine, and went after her.

The backyard was full of boys in swimming shorts. They were crowding around Will, whose dark-skinned shoulders were gleaming with water or sweat. Will was holding up his right hand, and so shocked was Fleur to see his bottom lip trembling and tears pouring down his face that she didn’t notice the blood at first. Then she saw the cut on the pad of his upraised index finger, from which blood was trickling into his clenched fist. Fleur was confused. It didn’t look bad enough to warrant all this fuss.

“What happened?” Millie shouted. “What happened?”

One of the boys glanced behind him and Fleur followed his gaze. On the stone flags a couple of meters from the edge of the pool was the portable crib that she assumed contained the R1 baby assigned to Millie, a girl whom Millie had named Rose.

“We were playing chicken,” the boy said, his voice tight and high with the knowledge that they had made a terrible decision, a decision from which there was no going back. “It was Ryan’s idea.”

“It wasn’t my fault!” a boy who must have been Ryan protested.

“Never mind whose fault it was,” Millie shouted. “What’s chicken? What do you mean?”

All at once Fleur knew exactly what they meant. Calmly but urgently she said, “They were daring each other to stick their fingers in Rose’s feeding hole. Only Will didn’t pull his finger out quickly enough and he got bit.”

Millie’s eyes widened in horror. “You idiot!” she screeched at her brother. “You stupid idiot!”

Will was blubbing like a baby, tears and snot pouring down his face. “I’m gonna get the virus,” he wailed. “I’m gonna become a biter.”

“No, you’re not,” Fleur said firmly. “If you get treatment within the first ninety minutes they can stop the infection.”

“Really?” Will said, his teary eyes stretched wide with desperate hope.

Turning to Millie, Fleur said, “He needs to go to hospital. Is your mum—”

But Millie was already wheeling toward the house. “Mum!” she screamed. “Mum!”

* * *

“He’ll be fine, Mum,” Millie said softly. “You’ll see.”

Millie’s mum, Clara, had once been a model. To Fleur, her mahogany-colored skin seemed to glow, as if with some inner light. She had thickened a little around the waist since her modeling days, but even now, in her forties, she was a breathtakingly beautiful woman. At this moment, however, she looked wretched, her finely boned face taut with worry, her hands quivering as they twisted a tear-dampened handkerchief into smaller and smaller knots.

Fleur was sitting on the other side of Clara, in a plastic chair against the wall of the waiting area outside a pair of sealed, gray double doors. Above the doors was a sign that read:

R1 INFECTION AREA

RESEARCH AND TREATMENT

AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY

“Millie’s right, Mrs. Hawkes,” Fleur said reassuringly. “The man at the Moorlands Facility told us they have these drugs called…” She wrinkled her nose as she struggled to remember. “Antinecrotics, which block and kill off the R1 cells. They’re like virtually a hundred percent effective.”

Clara Hawkes nodded vaguely, but she shot a venomous glance toward Andrew, who was lying silent and still in his crib on the seat next to Fleur. “I don’t know why they let you girls have those damn things in the first place. I always said this project was a bad idea.”

Fleur stayed silent. She knew it wasn’t the right time to say that the babies weren’t to blame, and that the situation had occurred purely as a result of Will’s stupidity. Clara had insisted that Millie leave Rose behind at the house, even though she would need feeding again in an hour or so. At first, Fleur had thought Clara was going to tell her that she couldn’t bring Andrew, either, but Millie’s mum had been so preoccupied with her panic-stricken son that she had made no comment when Fleur placed Andrew’s crib on the middle seat in the back of the car.

They had been at the hospital now for over an hour, waiting for news. The bearded doctor who had spoken to them when they first arrived had told them that Will would be treated immediately, but that they would have to monitor him for a while until they were sure that all traces of the infection had been eradicated.

“How long will it be before you know for sure?” Clara had asked.

“It depends entirely on Will’s response to treatment,” the doctor had replied smoothly. “Based on past experience, it could be anything between one and six hours.”

In the seventy minutes or so since their arrival, a couple of white-coated doctors had entered the Infection area, having first tapped entry codes onto a keypad on the wall, but no one had come out. Fleur looked at her watch. It was almost 3:50 P.M. Her mum wasn’t due to pick her up until six, but if nothing happened within the next hour she’d have to call her and tell her what was happening. She looked at Andrew lying in his crib. She couldn’t say she felt any particular affection for the boy, but she no longer felt the anxiety and repugnance she had experienced in the presence of the R1 infants a week ago. In that respect, she supposed, the project had been a success, whatever Millie’s mum thought. She looked around as the double doors to the Infection area hummed, clicked, and then began to open as someone pushed them from the other side. The person who emerged was the last one she expected to see.

“Mum!” she gasped.

Jacqui froze, a look of horror on her face. It was the expression of someone who has been caught red-handed, someone who has nowhere to hide. As if reading her daughter’s mind, Jacqui blurted out the question that was on Fleur’s lips: “What are you doing here?”

“We were…” Fleur said, trying to pull her jumbled thoughts together. “I mean … Will got bit … Millie’s brother, I mean.” She frowned. “Why aren’t you at Aunt Valerie’s?”

For a moment Jacqui looked trapped—then her shoulders slumped. “Oh well, I suppose it had to come out sooner or later,” she said.

“What did?” asked Fleur.

Jacqui gave her a strange look—a sad, resigned look that made Fleur’s stomach clench.

Then, quietly, she said, “We need to talk.”

* * *

Sitting hunched over, as if weighed down by a burden of unspoken revelations, Jacqui reached out and took Fleur’s hands. She drew a long breath into her lungs and slowly expelled it, and then she said, “I lied. Your father’s not dead.”

The instant Jacqui said the words, Fleur knew she should have been expecting them. Yet, they hit her like a bolt of lightning. She jerked in her seat; her mind reeled; her world flipped upside down. She gripped her mother’s hands hard to stop herself from falling, and from somewhere faraway she heard her own small voice asking, “So why did you say that he was?”

Jacqui sighed and slumped lower in her seat, as if she had been inflated by nothing but secrets and regret for the past seven years and it was all now leaking out of her.

“Because he wanted me to. Because he couldn’t bear the thought of you seeing him like … like that.” Her voice dropped to a whisper. “But I couldn’t bear to let him go. I knew there was research going on. I knew that scientists and doctors were trying to find a cure for the virus. And if I’d given the order for your dad to … to be dispatched and then they’d found a cure…” She shook her head. “I would never have forgiven myself.”

Fleur didn’t know how to feel. Didn’t know whether to be angry or happy, horrified or betrayed. “We could have helped you,” she said, “Elliott and me.”

Jacqui shook her head. “It wouldn’t have been fair on you. You were just a little girl. I thought a clean break…”

Fleur said quietly, “But you let Elliott think … you let him say all those terrible things to you.”

“It was the best way,” insisted Jacqui. “The only way.”

Another short silence, as if the conversation were too big or too painful to be handled in anything other than bite-size chunks.

Eventually Fleur said, “And what about now? Will you tell Elliott now?”

“Will you?” countered Jacqui.

Fleur shook her head. “I don’t know. I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to think.”

“You don’t have to decide anything yet. Why don’t you just … get used to the idea first?”

Fleur let her gaze slide past Millie and Clara, sitting a dozen or so meters away, to the gray doors beyond them. “Is Dad in there?”

Jacqui nodded.

“So you come here every Friday? You don’t go to Aunt Valerie’s at all?”

“I see your aunt Valerie in the mornings,” said Jacqui. “We have lunch and then I come here. Valerie used to come with me at first, but she found it too upsetting. Now it’s just me.”

“What do they do to him in there?” Fleur asked. Anger sparked in her and she welcomed it, grasped it. It was a real emotion, something to anchor herself to. “Do they experiment on him?”

“No!” Jacqui’s denial was loud enough to make Millie and Clara turn their heads. Controlling herself, she said, “No, I wouldn’t allow that. They try to cure him, that’s all. Anything new they discover, any breakthroughs they make, your dad’s one of the first to benefit from it.”

“So he’s a test subject,” said Fleur.

“You make it sound bad. It’s not bad. They’re trying to make him better. They’re not hurting him. I make sure of that. He has a good life … for what it is.”

Another silence. Fleur felt sick and hollow. She was finding it all hard to digest. Finally she said, “Have they made any progress?”

Jacqui didn’t answer immediately. And then hesitantly she said, “I think so … yes.”

“I want to see him,” said Fleur.

Jacqui looked alarmed. “I don’t know if that’s a good idea.”

“He’s my dad. I want to see him. You can’t tell me he’s alive and then not let me see him.”

Now Jacqui looked anguished, torn. “I’m not being mean,” she said. “I just … I don’t want you upset, that’s all.”

“I can handle it,” said Fleur stubbornly. “I’m old enough.” She paused and then said with quiet conviction, “I want to see my dad.”

Jacqui stared at her for what seemed to Fleur a long time. She stared at her as if she had never seen Fleur properly before, as if she had not noticed until now how quickly her little girl had grown up.

Then she gave a short, decisive nod. “Okay,” she said. “Come with me.”

She stood up and walked back toward the gray doors. Fleur picked up Andrew’s crib and followed her. As they passed Millie and Clara, Millie half reached out. “Hey, you okay?”

“Fine,” said Fleur, giving Millie no more than a glance. She could see that her best friend was brimming with questions, but she averted her gaze, unwilling to give Millie any encouragement to ask them right now. Instead, Fleur watched Jacqui stab a code number into the keypad on the wall, and then she followed her through the gray doors.

* * *

Dr. Beesley had hair growing out of his nose. Fleur couldn’t stop staring at it. She felt not quite real. She felt as if this were a dream, or as if her thoughts were floating like balloons a few meters above her head. She shifted her gaze to Dr. Beesley’s plump, wet lips in the hope that if she saw the shape of the words he was forming, she would find it easier to concentrate on them.

“We think there has been some definite progress,” he was saying to Jacqui. “Thanks to the new drug treatment, Andy’s aggression levels are considerably reduced, and he seems far more responsive to his surroundings and to both auditory and visual stimuli. Dr. Craig informs me that you were there when they played the music this morning?”

Jacqui nodded. “Yes. It seemed to me as if Andy was listening to it. Aware of it, at least.”

Dr. Beesley nodded. “And he’s the same with voices. He no longer automatically identifies a human voice as simply the location of a potential food source. When we talk to him he appears to listen. Sometimes I swear he understands every word I’m saying.” He chuckled at his own joke, then asked, “Did he establish eye contact with you this morning?”

“No, I … no,” Jacqui said.

“Well, hopefully that will come. There have been brief indications of it already. Nothing conclusive, but we remain cautiously optimistic—as ever.” Finally, Dr. Beesley turned his attention to Fleur. “So you’ve come to see your father, little lady?”

Fleur frowned and for a fleeting moment considered telling the doctor that she was thirteen, not six. Instead, she nodded.

“Very good. First contact with an infected loved one is never anything less than an emotional experience, but if you’re prepared for that, I’m sure Andy will benefit from your visit.”

“He might not,” muttered Jacqui.

Dr. Beesley frowned. “I’m sorry?”

“Fleur found out about Andy by accident. Until twenty minutes ago she thought he was dead.” Jacqui took a deep breath. “Now she insists on seeing him, though personally I’m worried how Andy might react. He never wanted his children to see him … well, you know.…”

“I see,” said Dr. Beesley slowly. “Well, the decision is yours to make. I would offer advice, but such encounters are entirely unpredictable. All I can recommend is that if Andy does start to show signs of distress, it might be best to beat a hasty retreat.”

“We will,” said Jacqui decisively.

“Could I see my dad now, please?” said Fleur.

A little taken aback at her directness, Dr. Beesley said, “Er … yes, of course. This way.”

He led Fleur and Jacqui along several corridors until they came to one that had a gate stretching from wall to wall and floor to ceiling. A six-digit code punched into yet another wall-mounted keypad opened the gate. Beyond were closed, numbered doors not unlike the ones at the Moorlands Facility. Dr. Beesley led them around the corner and halted outside door number 5.13. Another keypad, another entry code, and the door clicked open.

With a sweep of his arm, Dr. Beesley invited Jacqui and Fleur to precede him into the room. Not knowing quite what to expect, Fleur allowed Jacqui to go first, and then followed, moving with a lopsided lurch because Andrew’s crib, which she was carrying by the handles, kept bumping against her thigh.

She found herself in what amounted to a smaller version of the Crèche at the Moorlands Facility. The anteroom was narrow, rectangular. A nurses’ monitoring station, currently unoccupied, was tucked up against the left-hand wall. Directly before them, opposite the door through which they had entered, was another wall made of what appeared to be thick, transparent Perspex. The white-walled room beyond that was twice the size of this one, simply furnished with a bed and a chair, both of which were bolted to the floor. There was a man lying on the bed, arms by his sides, unmoving. Fleur could see him only in profile, but she gasped in recognition.

“Dad!”

He was thinner than she remembered him, and his skin had the same mottled, blue-gray hue of all R1 sufferers. Dr. Beesley appeared from behind her and indicated a small metal grille on the wall above a pair of buttons. “You can speak to him if you like. Just press this button here.”

Fleur didn’t move. All at once she felt uncertain, a little overwhelmed by the situation. Unable to tear her eyes from the motionless figure, she was only half aware of her mum stepping across to the grille and thumbing the button.

“Andy.” Jacqui’s amplified voice made Fleur jump. “There’s someone here to see you.”

To Fleur’s consternation, the figure on the bed stirred. Her father’s leg twitched slightly; his fingers moved like worms probing blindly for the light. He looked like Frankenstein’s monster coming alive in some of the old movies she’d seen.

“Say hello to your dad, Fleur,” Jacqui said softly. “Don’t be shy.”

Fleur licked her lips. She put down Andrew’s crib and moved across to stand beside her mum. She felt as if she were floating, drifting. Jacqui, her thumb still on the Talk button, smiled encouragingly.

Fleur bent her head toward the grille. Her mouth was dry. She licked her lips again. Finally, she croaked, “Hello, Dad. It’s me. It’s Fleur.”

Slowly, like an old man waking from a deep sleep, her father rose from the bed. First of all he sat up, and then he turned, his legs swinging clumsily over the side of the mattress, his feet brushing the floor.

Fleur stepped back, unable to stifle a small, involuntary bleat of distress. Viewing her dad full-on for the first time, she saw that his face was slack, expressionless, his mouth hanging open, his eyes blank and staring. There seemed to be nothing at all of the father she remembered in there. No life, no personality. He seemed nothing but a walking lump of dead flesh, a receptacle for the virus that animated him. He dropped his weight forward onto his feet, swayed for a moment, and then clumped heavily toward them.

Fleur took another step back and then felt a hand—her mum’s—in the small of her back.

“It’s all right,” Jacqui said soothingly. “Don’t be scared.”

Fleur braced herself, then stepped forward. Her dad shuffled right up to the Perspex wall, so close that if he had been breathing, a mist of condensation would have formed on its transparent surface.

“Talk to him,” Jacqui whispered. “Go on.”

Fleur didn’t know what to say. Then, hesitantly, she muttered, “I know you didn’t want me to come here, Dad, but it isn’t Mum’s fault, so don’t blame her. I kind of found out about you by accident, and I made her bring me. I’m thirteen now and … and I’ve missed you, Dad. I’ve missed you a lot.” Suddenly she felt emotion welling inside her and did her best to swallow it down. After a few seconds she continued. “I know you’re sick, but it isn’t your fault, and you shouldn’t be ashamed. The people here are trying to make you better. They say you’re doing really well.”

She wasn’t sure her words were getting through. Certainly there was no change of expression on her dad’s face. But suddenly his eyes flickered and slid to the left, making Jacqui gasp.

“He’s looking at the baby,” she hissed. “Show it to him.”

Fleur turned, to find that Dr. Beesley had already picked up the crib and was handing it to her. She took it from him and turned with it in her arms, presenting it to her dad like an offering.

“He’s not mine,” she said. “I’m looking after him for a week, as part of a school project. He’s sick like you, Dad, but everyone’s working really hard to come up with a cure to make you both better.”

Her dad continued to stare at the baby. He seemed mesmerized by it. Then, slowly, his gaze shifted. His pale, bloodshot eyes rolled up and all at once he was staring at Fleur. Staring right at her.

Behind her, Fleur heard Jacqui whisper, “I don’t believe it. He’s looking at you. Oh, Fleur, he knows who you are.”

Fleur continued to stare into her father’s eyes, their faces—separated by the Perspex wall—less than a meter apart. She smiled. “Hello, Dad,” she said softly. “Remember me?”

Moving as if in slow motion, Andy raised his right hand and pressed it, palm forward, against the transparent wall. Lowering the crib to the ground, Fleur echoed his action, raising her left hand and placing it against his, so that they were separated by nothing more than the thickness of the barrier between them.

Moving as if in slow motion, Andy raised his right hand and pressed it, palm forward, against the transparent wall. Lowering the crib to the ground, Fleur echoed his action, raising her left hand and placing it against his, so that they were separated by nothing more than the thickness of the barrier between them.

Suddenly Jacqui let out a gasp, and Dr. Beesley, his voice hushed with wonder, said, “Oh my God. Would you look at that.”

Fleur was looking at it. She couldn’t tear her gaze away from it, in fact. As the single tear brimmed from her father’s eye and trickled slowly down his mottled cheek, she didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

* * *

Copyright © 2012 by Christopher Golden

21st Century Dead is available now at Amazon.com.

This story was provided and by and published with permission from the publisher, St. Martin’s Griffin.

Tags | zombies