Translating The Walking Dead to Prose

Posted on November 29, 2011 by Flames

All zombies are created equal. All zombie stories are not.

From its humble beginnings as an indie comic book, The Walking Dead has become a pop culture juggernaut boasting New York Times–bestselling trade paperbacks, a hit television series, and enough fans to successfully take on any zombie uprising.

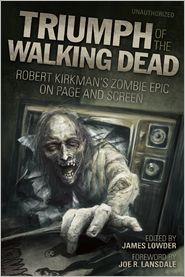

Triumph of The Walking Dead explores the intriguing characters, stunning plot twists, and spectacular violence that make Robert Kirkman’s epic the most famous work of the Zombie Renaissance.

Flames Rising is proud to present an exclusive excerpt from this book. The Walking Dead novels’ co-author Jay Bonansinga provides the inside story on translating the comics into prose.

A Novelist and a Zombie Walk into a Bar

A dear friend, who also happens to be a Hollywood talent manager, rings me up one day last summer and babbles into the phone: “Some people I know are shopping for a novelist to help write a book based on a comic that’s being developed into a TV series. You with me so far?”

A dear friend, who also happens to be a Hollywood talent manager, rings me up one day last summer and babbles into the phone: “Some people I know are shopping for a novelist to help write a book based on a comic that’s being developed into a TV series. You with me so far?”

I mumble something like, “Um . . . I think so.”

“Anyway,” he goes on, “you would be working with the guy who created the comic, who is somewhat of a big shot, and you know, this deal could very possibly open many doors across the southern region of California. And when I heard they were looking for some author with horror chops who can play nice with others and has a really sick, disgusting imagination and is somewhat morally challenged . . . I naturally thought of you.”

“Uh huh,” I say. “And may I be so impertinent as to ask the name of the comic?”

“Ever hear of The Walking Dead?”

“The Norman Mailer book?”

“That’s The Naked and the Dead . . . and I said comic.”

“There aren’t any naked people in this?”

“Are you on something right now?”

“I’m kidding.” I take a deep breath. “Of course I’ve heard of The Walking Dead . . . cripes! Who do you think I am, your dad? It won the Eisner Award and it’s like a marathon of great, lost Romero movies all strung together . . . but better . . . it’s like the picture George Romero would make in heaven on acid with God as his cinematographer.”

After a long, exasperated pause, my buddy says, “Shall I take that as a Yes, you’re interested?”

Robert Kirkman’s epic survival saga The Walking Dead lives in its own graphic stratosphere—a rarefied yet austere visual canvas that screams out for translation into other media. Among the iconic roster of superstars who have rushed in to decode Kirkman’s muscular visual universe are Hollywood luminaries Frank Darabont and Gale Anne Hurd, whose basic-cable phenomenon of the same name pulls off a major coup: it captures the human drama beneath all the rotting flesh and ultimately channels the power of Kirkman’s two-dimensional frames into the bland, parochial world of the small screen.

Producers of the mega-smash AMC TV series have made two important discoveries: 1) the spiritual center of the comic series—a human story playing out amid all the gore—translates well to the intimate confines of television; and 2) the ingenious way Kirkman builds big cliffhanger moments into splash pages that end each issue works like gangbusters on the tube. After a fleeting first season of only six episodes—an introduction to the Kirkman universe so ephemeral it almost seems like a freak accident—viewers were hungrier than reanimated corpses for more red meat.

Now we come to the second re-imagining of The Walking Dead, a trilogy of all-original novels based on Kirkman’s mythos, which take readers deeper into the narrative waters and all the rich tributaries branching out of the central story. Commissioned to coincide with the highly anticipated second season of the AMC series—premiering on Halloween 2011—the books are the latest milestone in the media crossover sensation.

Now we come to the second re-imagining of The Walking Dead, a trilogy of all-original novels based on Kirkman’s mythos, which take readers deeper into the narrative waters and all the rich tributaries branching out of the central story. Commissioned to coincide with the highly anticipated second season of the AMC series—premiering on Halloween 2011—the books are the latest milestone in the media crossover sensation.

In some ways I feel as though I was born to collaborate with Mr. Kirkman. A film school brat, I was weaned on EC comics—Vault of Horror, Tales from the Crypt, et al.—and after graduating, I spent years writing short horror stories for magazines such as Grue, Cemetery Dance, and Weird Tales.

After publishing my first novel, The Black Mariah, in 1994, I had the absolute sublime pleasure of working with George Romero on the film adaptation of said book. I will never forget landing at the Fort Myers airport for a story meeting at George’s house in Florida and seeing this big, burly grizzly bear of a man loping toward me with a huge smile. “Let me carry that,” he said, eyeing my suitcase. I was aghast and euphoric in equal parts. The thought of my childhood hero schlepping my luggage was my first lesson in a strange dichotomy: those who create the darkest, nastiest, harshest fictions are in true life the biggest pussycats.

Robert Kirkman is no exception. After working with him on the first installment in this triptych, I am stunned by how gracious, humble, and down-to-earth the man is. But the more I think about it, the more I conclude that this kind of unexpected sweetness—as is the case with George Romero—is Kirkman’s secret weapon.

This decency and plainspoken nature is actually what has enabled Robert Kirkman to reinvent an entire genre in comic book form.

After encountering the Walking Dead comics, no reader will ever be able to watch a zombie film, or read a zombie story, or just generally think of zombies in quite the same way. Without spoiling the main narrative for anyone living under the proverbial rock, suffice it to say that the comic paints a familiar picture with unfamiliar colors and tones. In the early issues, a small ragtag band of everypeople find themselves struggling to survive an inexplicable plague of cannibalistic, reanimated corpses. But the thing that instantly sinks a hook into readers—and is probably responsible for turning the comic into a milestone of the genre—is an unexpected humanity.

The characters of The Walking Dead are not mere characters; they are people. They are terrified, and they are morally sickened, and they long for deliverance, and they love their children, and they will do anything to protect their families. In other words, unlike the marionettes of most zombie books and movies, these people act like . . . well . . . real people.

“So . . . you got a name?” the lonely main character, Rick Grimes, whimsically asked a horse on which he rode through a desolate landscape in an early issue. The former police officer had just awakened from a coma after being shot in the line of duty, and now he was frantically searching the apocalyptic byways for his family. “I held her hand the whole time,” Grimes later recounted for the uncomprehending animal, describing his wife’s labor and the subsequent birth of his son. “There were some complications . . . and she had to get a cesarean. I was really worried . . .” Grimes eventually chokes on the words and can’t go on . . . but in a way he discovers right then why he must go on . . . and why we the readers must turn the page!

This is the keystone of The Walking Dead’s power: an unexpected tenderness in the characters. Because of this, the stakes of this story are raised incrementally with each page. You care a little bit more. You empathize. And, perhaps most importantly, you realize that this empathy is what makes the next eruption of trademark zombie-splatter all the more horrific.

Kirkman and his team of artists keep the visual strategy of the comic simple and linear. The style brings to mind the kitchensink realism of Bernie Wrightson of Swamp Thing and Warren horror comics fame. Both literary and filmic devices are put to good use. As is silence: characters brood and ruminate wordlessly in many of the panels, often captioned by a simple and inscrutable ellipsis. At other points, the comic’s mise-en-scène of epic filmmaking conjures memories of Sergio Leone and David Lean. Intimate close-ups widen out to panoramic landscapes of vast prison yards and urban outskirts. Huge empty skies are stitched with Hitchcockian crows.

The Walking Dead begs comparison to both EC horror and end-of-the-world epics such as Earth Abides, The Stand, and I Am Legend, but, more than anything else, it is the character-driven pathos that truly elevates the series into transcendent territory. It is also the thing that fuels the adaptation Robert and I tackled in the early months of 2011.

I wish I could say we labored with Sisyphean effort to translate the panel-bound world of the Walking Dead comic into the ethereal, cerebral, non-linear world of prose. I wish I could say we ingeniously contorted the visual details of the comic book into exotic allegories and literary equivalents. But the truth is, the mythos of The Walking Dead made the leap to fiction with the ease of a bullet passing through the rotten gray matter of an animated corpse. Maybe this was due to the relentless forward motion of Kirkman’s narrative. Perhaps it was because of the meticulous simplicity of the plot—every twist, every turn, every shift in point of view, every “money shot” completely, utterly motivated.

Technically a comic book’s closest cousin is the feature film. In a movie, a story is told with pictures and dialogue. Things happen, and people react to those things . . . and everything occurs in the here and now, with minimal, if any, use of devices such as flashback (a staple of prose). Of course, there are movies that employ voice-over narration—think of Philip Marlowe recalling how dark and stormy the night was when that crazy dame walked through his door—but, again, such devices are actually quite rare. Even in the case of movies with a narrator, the main body of the story unfolds in the present tense.

Such is also the case with the comic book medium. Granted, there are occasional thought bubbles, as well as boxes and sidebars containing Godlike, omniscient narration, but for the most part, comics—especially modern comics—show rather than tell. Instead of revealing a character’s thoughts (or providing clunky, whimsical narration in the style of the Crypt-Keeper), the modern comic shows you internal life through external action.

Such is also the case with the comic book medium. Granted, there are occasional thought bubbles, as well as boxes and sidebars containing Godlike, omniscient narration, but for the most part, comics—especially modern comics—show rather than tell. Instead of revealing a character’s thoughts (or providing clunky, whimsical narration in the style of the Crypt-Keeper), the modern comic shows you internal life through external action.

The Walking Dead abides by this axiom with almost religious fervor. Nobody pauses to think . . . they just do. They love, they hate, they struggle, they dream, they plot, they screw up, they live, they die, they kick zombie ass, they get devoured . . . all of it in real time.

Here’s the kicker: Despite the inherent differences between comics and prose, Kirkman and I found the act of rendering The Walking Dead into a novel fascinatingly expedient. The way the visual flow of the comic is organized cries out for analogous organization in a book. The cliffhanger splash pages suggest twist endings to chapters. The density of panoramic landscapes leads to cinematic scene-setting. The gruesome detail of cadaverous faces and all the vivid carnage demands visceral description. And Kirkman’s lean, straightforward way with dialogue looks and sounds terrific on the printed page—a mixture of Cormac McCarthy and Martin Scorsese.

Conventional wisdom says that novels—unlike movies, television, comics, or theater—are internal. You get inside the thoughts and motives of the characters. In novels you are free to present your story in non-linear fashion, jumping back and forth in time and point of view. Novels are digital rather than analog. They are everywhere all at once. They are impressionistic rather than structural. To put it another way, a novel is inside-out instead of outside-in. You tell your story from inside the characters, and the power comes from an accumulation of detail.

Even the action-oriented adventure books of yesteryear—beginning with the turn-of-the-century penny dreadfuls and continuing through the pulps of the 1950s—told their stories through the steely nervous systems of their lantern-jawed heroes. Granted, the internal stream-of-consciousness of a Doc Savage or a Conan the Barbarian were not exactly grist for Freudian analysis. But the form itself necessitated that the reader feel the sting of a poison-tipped spear from inside the synapses of the hero.

On a deeper level, the novel can also be about something else altogether. In this chaotic age of the internet, gaming, and social networking, the novel—more than ever—is the most interactive of all media. It is about getting inside the thoughts and motives of the reader. Subtly, insidiously, sensually, sneakily, the novel is all about touching off the flames of the imagination.

As William Burroughs said, “Language is a virus from outer space.” And what a good novel does is infect the inner space of a reader with images, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures.

Happily, the universe of The Walking Dead is not only born out of a very direct, linear approach to narrative, but is also evocative of myriad sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures—most of which are latent, hiding within the panels, alluded to in the dialogue, suggested by the narrative.

The fictional version teases these sensory details into the foreground. A reader is spared nothing. The senses are assaulted by the side effects of the plague. Explanations are eschewed in favor of a constant triangulation of sensory input. A floor is sticky with gore, giving off an oily black aroma as the characters investigate a deserted room buzzing with the vibrations of bluebottle flies and the echo of something moaning in the basement.

This profusion of sensory detail ultimately dictated the stylistic approach that Kirkman and I adopted for the novels.

Not only do the Walking Dead novels move with the inertia of a fever dream—all told in the present tense, jumping from one point of view to another with the quick-cut velocity of a movie montage—but the sensory details suggested in the panels of the comic are amplified, intensified, enriched. Like particles charged with radioactive half-lives, the flies on a corpse lead to internal trauma among eyewitnesses, which leads to madness, which leads to the slaughter of more corpses and the geometric population growth of flies. The world now has flies on it, the core of civilization rotting from the inside, personified by the internal atrophy of the characters. And always at the center of the action is the single most important symbol, the engine powering the conflict from the inside as well as the outside, the moldering, festering raison d’e^tre around which everything revolves, the key to the whole damn thing . . .

The zombie.

As a novelist, I cut my teeth during the horror boom of the 1980s—that heady time when anything with a lurid foil cover and the words “evil” or “phantom” in the title ruled the bestseller list with the consistency of death and taxes. I learned to write by gobbling up Stephen King, Peter Straub, Clive Barker, Joe Lansdale, David Schow, and Skipp & Spector. And I started getting published at the cusp of the splatter-punk bubble, when guys like Edward Lee and Rex Miller were pushing the envelope of anatomically incorrect gore. But I think the greatest influences on my writing were the archetypes of supernatural horror: ghosts, vampires, werewolves, demons, and manmade monsters of all makes and models.

Popularized first in the classic Universal Studios films of the 1930s and 1940s, these mythological beings have been cash cows for nearly a century. But historically, their origins go back all the way to the nineteenth century, springing from the quill pens and genteel sensibilities of Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker.

On the page, the archetypes have aged well because they have deeper meanings than mere bogeymen. The vampire—a potent symbol of repressed human sexuality—finds new and romantic iterations in teenybopper romances such as Twilight. The devil and his minions—those pesky personifications of our baser instincts—are alive and well in works such as William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. Ghosts—our stubborn, guilty past consuming the present—continue to haunt literature, both highbrow and low. But what about the lowly, hapless zombie? How does this archetype fit in? What does a zombie represent culturally? Why hasn’t it enjoyed more days in the literary sun? One is hard pressed to name a zombie classic in book form. Stephen King’s Cell? Max Brooks’ World War Z? These are fine books, but I’m not sure we have yet seen a literary zombie masterpiece . . . and the reason may be as simple as the problem of comparing oranges to rotten apples.

The zombie is the coin of the visual realm—a conceit of movies and comic books. By design, the archetype has no “there” there—zombies are eating machines, dead inside and out, with no purpose other than devouring the living and multiplying. Even their appearance has a sort of uniform, machine-stamped quality—albeit a gruesome one—that brings to mind the way death makes us all the same. Namely . . . gross and inert.

Keep in mind that I’m not referring here to the gothic voodoo wraith as depicted in subtle cinema such as Val Lewton’s I Walked with a Zombie. I’m talking about George Romero’s lurid concoction first unleashed on the war-weary, turbulent, paranoid society of the late 1960s. The rainbow coalition of shambling, slow-moving, cannibal roamers in Night of the Living Dead resonated deeply in the American imagination over the next four decades . . . and they resonated for a reason.

Romero’s zombies represent the wolves at our doors. They represent your mortgage, your car payments, your pending divorce, the suspicious lump under your skin—the things that just keep coming at you and will not stop until you are toast. Xenophobia, the collapse of society, your toilet backing up— these are the dream symbols personified by the undead.

Robert Kirkman knows this well. In his comics he constructs a human underground fighting to retain its humanity in the face of the wolf pack—and the moldering beasts just keep on coming and coming, as inexhaustible as cancer cells. The depiction of the zombies in The Walking Dead are lavish, Grand Guignol works of art. The sunken faces are lovingly rendered, the hollow cheeks and blank eyes carefully delineated to distinguish one monster from another. It’s like a nightmarish catalogue of exotic fighting fish.

Robert Kirkman knows this well. In his comics he constructs a human underground fighting to retain its humanity in the face of the wolf pack—and the moldering beasts just keep on coming and coming, as inexhaustible as cancer cells. The depiction of the zombies in The Walking Dead are lavish, Grand Guignol works of art. The sunken faces are lovingly rendered, the hollow cheeks and blank eyes carefully delineated to distinguish one monster from another. It’s like a nightmarish catalogue of exotic fighting fish.

And this is the key to our translation.

Until Robert Kirkman decides to include scratch-and-sniff panels on his comics, the non-visual senses will be the stars of their prose counterpart. Through meticulously calibrated description, we layer the smells and sounds and textures. This is how we translate something that is purely visual, by writing it in “odorama”—getting inside the senses of the readers. In other words, in the purely visual world of the comic, we must see Rick Grimes reacting to an odor—“Phew!”—in order for us to smell that odor. In the novels, we go straight for the nose.

Have you ever wondered what a warehouse filled with hundreds of upright cadavers would really smell like? Or have you thought about what a chorus of thousands of zombies all moaning at the same time would sound like? Maybe you’ve ruminated about what the exact texture of brain matter is like after getting sprayed across the inside of a windshield.

Doesn’t everybody wonder about these things?

The best part of this sensory feast, however, is for those who hunger to go deeper into The Walking Dead backstories. The trilogy—the first installment of which is available from St. Martin’s Press—is no mere tie-in. These are not standard novelizations that follow a screenplay or comic note for note. Our books—courtesy of the endless well of Kirkman’s fecund imagination—explore the origins of mysterious characters and the tantalizing secrets and relationships only alluded to or fleetingly glimpsed in the comics.

As a novelist, I could not ask for a more exciting thrill ride. Six months after that original call from my Hollywood friend in which he floated the idea of going on this amazing journey with Robert Kirkman, my pal calls me back. “Hey, Boopie,” he says. “How’s the zombie business?”

“We’re killing ’em in Poughkeepsie,” I tell him.

“What stage are you at?”

“I’m close to writing ‘The End,’” I say. “Right now I’m in a warehouse full of dead people.”

“What’s it smell like in there?” he asks.

“You don’t want to know.”

“C’mon, I can take it.”

“Okay. It smells like a combination of human feces and bacon cooked in pus.”

After a long pause—during which I can hear a faint gagging noise—he says, “God, I hate you . . . I have a lunch meeting today at Greenblatt’s Deli, and had planned on the chicken liver.”

“You asked.”

“I’ll have that smell in my schnoz for weeks.”

He cannot see me smiling. “That’s the idea, my friend . . . that’s the idea.”

Jay Bonansinga – 2011

Jay Bonansinga is a national bestselling author, screenwriter, and filmmaker, whose directorial debut, Stash, premiered in 2010. His 2005 novel, Frozen, is in development as a major motion picture, and his latest book, Perfect Victim, is an alternate title for Book-of-the-Month Club. He has worked with George Romero and has won major film festival awards, including a Gold Remi at the Houston International WorldFest and a “Best Comedy Feature” at the Iowa City Landlocked Film Festival. Jay’s 2004 nonfiction debut, The Sinking of the Eastland, won the Certificate of Merit from the Illinois State Historical Society, and his forthcoming nonfiction Civil War thriller, Pinkerton’s War, is due out from Lyons Press in late 2011. Online at jaybonansinga.com.

Tags | post-apocalyptic, zombies