We Can Make Them Look Like Anything – Violet Core RPG

Posted on October 19, 2024 by Flames

Violet Core is a sapphic focused ttrpg about sad mecha piloting lesbians dueling each other and making out while stranded in space. Drawing inspiration from the absolutely wonderful visual novel Heaven Will Be Mine as well as GunBuster, Zone of the Enders and Knights of Sidonia. It focuses the dramatic tension between friends, rivals and comrades. It’s a game whose beating heart is deeply lesbian in a way that is a touch tricky to put into words…its indelibly infused. It’s a game preoccupied with a looming horizon of destruction and what we do in the face of calamity.

Currently funding on Kickstarter with less than a week to go as of this post! Today the Flames Rising crew is thrilled to offer a guest blog spot to Kiki Kwassa.

“We Can Make Them Look Like Anything: Sapphic Love and Longing Inside My Giant Sexy Robot Body, or I Can’t Get Laid in my Giant Robot, But I Can Always Get F*cked aka an essay about Violet Core”

by Kiki Kwassa

Something I think is always funny about roleplaying game books is the constant struggle they must have with pronouns, with voicing gender to their prospective reader. I remember reading the 3rd edition DM’s guide and seeing them explain that they would switch between male and female pronouns by paragraph. Others would pre-empt any questions by saying that yes, they recognize the hobby is not all male and of course they cannot expect every reader to be a man and indeed, women playing roleplaying games are not rare and SURE there are lots of women bylines in the industry already so it would be silly to even presume such a thing no matter what the author’s own experience or confirmation bias might hold true but they are ONLY using exclusively male pronouns for SIMPLICITY and REST ASSURED if there was some solution to this glaring flaw in the English language then they would OBVIOUSLY be using that so get off of my back, okay?

If there is any truth in the joke that playing pen and paper RPGs will make you gay, or trans, or both, or something else even scarier, it rests in showing folks that the language we often use to describe things we take for granted as solid and platonic is, in fact, not completely accurate. It is not all encompassing, and in fact it is possible to embody an experience that is not our own, even to embody an experience we might not yet have a vocabulary for but can develop as we consider sensations and thoughts that would otherwise be impossible. RPGs open our eyes to realities we could never conceive of until we first imagined them in the context of a different person, an other, that we are then called on to become.

All of this is to say that I wonder how many will realize their own sapphic nature by playing Violet Core.

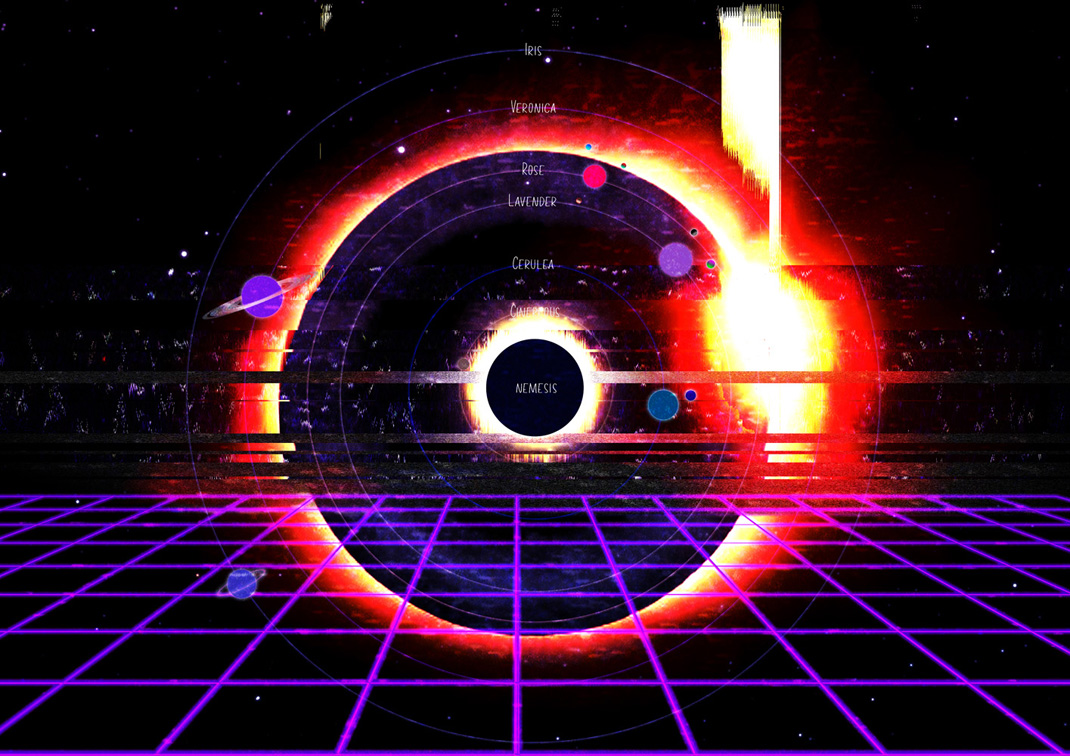

The folder I received for review begins with a setting primer that lays out a world that is, in fact our own. It’s date is murky, but the location is essentially our star system. Just a version of our star system that is bigger. We start here to venture into one of the two great aesthetic pillars of Violet Core. There are certain themes that resonate over and over in this game, a sign of a well crafted design. We get one of the first ones in the Nemesis Star Hypothesis that is the game world’s genesis. For folks who don’t know, the idea of the Nemesis Star is that Sol is a twin, with a sister star that forms a binary system. The two orbit around each other, and in their elliptical cycle come close enough that one brushes up onto the Oort cloud, releasing a wave of cataclysmic impacts through the planets of both systems as comets are dislodged and head out toward the two stars. I like to call this sort of sci fi speculation ‘stiff’ sci fi. It’s not necessarily hard sci fi and does not want to ask the same questions, and it is not soft sci fi, it clearly wants to anchor things a bit harder into possibilities that we could credibly hear ourselves during a particularly bad news report from some particularly scared astrophysicists. It’s a flavor of sci fi that feels distinctly retro, before the hard/soft split got as noticeable as it feels it is these days. It harkens back to the purported Golden age of these sorts of stories and even the name Nemesis Star feels torn right out of a 60s paperback.

The other big aesthetic pillar of the game is its queer nature. Specifically, its nature as something inherently gay and female. It is not subtle, but it is clever. All of the names feel right, and while the author Sarah Carapace explicitly wants it to be understood that the society of the nemesis Star’s earth equivalent is just as patriarchal, just as chauvinist and reactive of our own greater Terran culture, she nestles this into a place where the words and language supports the story of our disaster lesbian protagonists and their equally disastrous and lesbian antagonists, deuteragonists, and others. Planets called Lavender, Cerulea, and Rose cradle space stations named Swan as mechanics and machinists called Dressmakers fashion giant robotic superstructures for pilots of exceptional skill who utilize the metaphysical power of their Violet Cores to communicate with each other through a parallel dimension called Subspace to take each other on in something that resembles warfare, or a rumble, or even a dance battle in machine bodies untethered by realities of gravity, with nearly immortal integrity, in defiance of mundane eyes and mundane natural law. Everything feels like that specific ideal of being sharp, dangerous, fragile, and unnaturally beautiful. It takes place in space because the powers on their original home planet, the place that they left to protect from the convergence of the two stars, have denied them a way back. Cerulea has closed the doors on them because they see them as a threat, a corrupting influence, a harbinger of possibly worse things that could happen if they let them even one step into their society. I have to believe the connections to the Lavender Menace were not just intentional but a little humorous. One must think of the world leaders on Cerulea, surrounded by gay planets, circling a gay star, and then all of these folks that they launched into space discovered an entire gay dimension and now they cannot under any circumstances be allowed back on planet because will someone think of the children? Reactionary 60s fear and horror feels inescapable to this setting, as does revolutionary 60’s queerness.

In all of this setting dressing, the big themes come out, as do the influences. If one has not been feeling the presence of the landmark visual novel Heaven Will Be Mine in my descriptions of existentially large mechs, space folk, reactionary world governments and an all pervading desire to be the hottest girl in this prison cell, Sarah Carapace is happy to spell it out. This game came out of love for that game, and that starting place is especially interesting to consider as we see the divergences. The big one, as I have kind of stressed, feels like the era the game operates in. Heaven Will Be Mine was, in many ways, a story placed in a sort of cyberpunk setting. It takes place in an alternate eighties, there are talks about the winding down of the space program, its visual cues come from that time specifically. While the author never comes out and /says/ that Violet Core takes place in an alternate time of the late sixties or even early seventies, I get the feeling that Sarah went that way instinctually. The aesthetics of a more butch friendly, less corporate minded space future make me think more of truckers than hackers. I like it a lot, and it does credit to how unique the setting is.

Working from the larger concept of the world, its geography, and its people, the narrative moment the game takes place in is also key to playing it. It takes place, again in a way that feels very reminiscent of a retro era, in a moment of decision and crisis. There are three main forces, each defined by how they are reacting to both the crisis and what decision they are taking for themselves. The crisis is what to do, having been shut out from going home. Our assorted space going peoples are the descendants of workers, researchers, and directors of a massive project designed to save the world of Cerulea from the convergence of stars, as well as from their own self destructive tendencies. By the time players get to enter the story, the spacefarers bear the scars of weathering multiple crises, dealt with their expulsion and the trauma of seeing the dream that united them shatter, formed into factions separated by ideals and distrust, rejected the concept of zero sum conflict they inherited from their homeworld, and now all bear a new and incredible technology that could change things forever. The question of course, is who will decide what the future of their people will be.

Ostensibly, the characters that players make are the ones at the forefront of this question. They represent pilots entrusted with this new technology, an amalgam of super science and awe inspiring forces beyond human understanding, called X-10s. They are not just the height of human technology but in some ways they represent the pinnacle of humanity, aesthetically, materially, they are almost idealized versions of human form and function. They ‘fight’ each other in a way that is more akin to territorial superiority displays. Fighting is not even the best word, it feels. They compete with each other. They struggle for control. They find rhythm, and assess their position. The point is not to kill, but to show to one side that if they continue to fight, they will lose everything. They are duelists, and they represent the will of their communities, competing to guarantee continuation of a way of life and a people that they serve through their exceptional, sometimes preternatural ability.

Of course, if the reader believes all that, your humble writer must point out that these stories are about people who are exceptional, traumatized, queer, and by design interesting. What this means is that all thoughts of ideals, strategy, and even existence can go out the window for the alternative of making out with your rival in the worst way possible for anyone who gets caught around or between it. The dual aesthetic pillars of the nemesis star hypothesis and the lesbian paperback romance collide, and their shared themes of mutual attraction, mutual destruction, tragic convergence and hard rejection are all ready for players to turn into explosive stories of thrown fights, double crosses, hypocritical allegiances to higher powers and high mindedness that come crashing down the moment that warmth, empathy, acceptance, and intimacy are offered.

The tightly woven themes extend to when the game moves out of the imagined, out of the shared narrative and to the shared table, into the realm of dice and stat sheets. Violet Core rests firmly in the realm of story games, and its systems offer meaningful choice in how characters define themselves but within rather narrow bounds of what the character is and what they are doing. What a player is capable of in the game is defined by a very small number of stats that modify a specific set of moves tied to the pilot background and class of X-10 that the player chooses.

All are part of a new generation of pilots, and indeed the fact that you are part of that new rising generation is important. Memory of Cerulea is something gained second hand. Moreover, the technology you are meant to control requires a new sort of pilot. There are three broad sorts of pilot archetypes, further subdivided into more specific experiences and circumstances.

Genebuilt are vat babies and wire women, augmented and controlled since birth to become the perfect human component to the X-10s. They are further divided into the Rat Bitch, a reject who did not ‘take’ and cannot be trusted as a conventional pilot but is still too useful to just get rid of or cut from the program, so they become a testbed. The attitude and trauma go without saying. On the other side of things is the VioletKind, for whom the process of being genetically engineered worked a little too well, and their already superhuman abilities became fortified by further abilities best characterized as inhuman. They are our newtypes, they are our starchildren. And like both, they seem to be pulled toward a new home away from Cerulea. Baseliners are as regular as folks can get in the setting, human born in space that are capable of piloting these freaky machines. Shining stars are kid prodigies and untouchable aces, Baseline Breakers are grinders pushing themselves to the limit and daring anyone to tell them they can’t hack it. Finally, there are Returned pilots. Pilots are important in this setting, anyone capable of handling an X-10 is an irreplaceable asset to the powers at odds with each other. The sort of injuries that would consign a regular spacer to a traumatic medical retirement or an unceremonious funeral are instead seen as repair bills for pilots. The Returned have come back from the brink of death so that they can get back into the robot.

Running through all these character archetypes is a theme of both exceptionality as well as a quality of the abnormal. Players do not get to be the ideal or even standard version of these pilots. Genebuilt are supposed to be built to spec. The Rat Bitch failed inspection, but also could not simply be liquidated or broken down for research. The Violetkind should have been a slam dunk success for the lab, but instead the pilot seems above all that they fight for and while the psychic powers should be an asset they instead feel like a liability. Baseliners simply aren’t supposed to be able to pilot these things, that’s why so much time and resources get pumped into making genetic super people, yet there’s the Shining Star making it seem like it’s easy and there’s the Baseline Breaker succeeding in spite of everything saying they should be a greasy smear on a dusty rock. More than anything, a pilot that is killed out in space should stay that way. But there’s the Returned, sitting in the ready room, prepping for another sortie. Everyone here is separated even from the people that they are supposed to be. Among those they are supposed to be like, they are alone, and only when they get to meet others who also represent degenerations or outliers can they feel kinship. Is all of this, I ask, queer enough for you?

I could honestly keep going. I could talk about the art, as the writer and designer for this game, Sarah Carapace, is also the lead artist and her style gives so much to these ideas. I could delve deeper into the three factions that the game’s conflicts are built around but that could fill its own overly long essay. There is so much to be said about how they can map to ideas of transition, ideas of community and the illusion of community, ideas of privilege and proximity to power. I could talk more about the X-10s, about the clear aesthetic inspirations and media that inform these specific permutations on such a storied set of archetypes that mechs in media about mechs draw from and converse with, but if the reader will permit me, your writer wants to at least get into the game’s system because on the one hand I am a little bewildered by it but on the other hand I am completely enthralled by its choices as well as the thematic resonances it shares with all this aesthetic nonsense that has already wasted so many words. Sadly, your humble writer does not have the same sense for organizing thoughts about game mechanics, dice probabilities, and player resource systems as for narrative concepts. All will have to bare with me.

Violet Core‘s mechanics come pretty clearly from the line of Apocalypse Powered games, and Monsterhearts specifically is named as a point of inspiration. One part of the mechanics that is a meaningful divergence from such games is that there is no roll result considered a ‘mixed success’. A roll can be rising, where good things are happening, or falling, where bad things are happening. When falling, a player can choose to ‘fall forward’, using a currency called boost chips to find success even as bad things happen. That’s basically the basics: you roll to find out what happens, a roll can be rising or falling, and if falling, a player can fall forward to gain some narrative control even as the Mistress (the game’s name for the nominal director of the game) makes things worse. The four key elements of the system are the dice, the modifiers, the moves, and the currencies. There are moves and modifiers that affect the pilot and the X-10, there is a specific subsystem of moves dedicated to Dueling that is apart from the more general system, and there are specific ways that the Mistress gets to use Moves, Modifiers, and Currencies in their work of facilitating the state of the narrative.

Moves are the start of all actions in the game, and can be seen as the sort of order of operations. They indicate the nature of a character’s actions, and the types of moves determine when and how often they may take those actions. Universal moves can be used once per scene, and are available to all pilots, therefore all players. Dueling moves are a specific subset of moves that are only used when dueling, and can be used as often as they are ‘activated’, which is to say when the conditions to use the move are met. They are also available to each pilot. Pilot and X-10 moves are specific moves chosen by the player to define their character and their character’s X-10s, the giant machine bodies that the pilots move, or are moved by each other. Again, rhythm and dynamics are the most important aspects of these moves.

What most moves call on you to do are to roll dice, or to modify the result or nature of the dice that you were about to roll or have rolled. Dice are, of course, a bit of a central thing to roleplaying games. They are not the central aspect of them, of course. They are tools, and are universally compatible. Their job is to provide a sort of analogue to the chaos of action, to simulate that whatever we plan, there is no accounting for the weather, or the warmth of other’s arms. Yet we still personify them. They are physical and tactile, unlike the rules that actually define the games we play. It is easy to find personality in them, and in Violet Core that tendency led down some interesting paths. The author asserts in this game that the d4, as compared to the others, is the gay die. It is certainly not one that is used often. Its limited number of results mean that it is not very useful for simulating a lot of variance, and four being its highest result means that in games that begin with the idea that big numbers are better, it is not an attractive one to have in the pool. But it is a very interesting little thing. It is triangular, it is distinctive, and the nature of its shape means it is just as easy to read the result on the top of the die, its vertex, or the bottom of the die, its base. Paraphrased from the author, they can get results on tops or bottoms. This seemed to delight Sarah Carapace, and using them as the base creates some very interesting possible results, when combined with how they can be modified.

As it is, the standard result on a die is 1 to 4. In the rules of the game, when a pilot makes a move that calls for a die roll, they are told which of a number of talents affects the roll. They roll a number of d4s equal to the value they have in the appropriate talent. If they get a 4, that result is a ‘Hit’ and the Move is successful. Any other result is a miss. When a player gets a hit, they are ‘Rising’, and depending on the move may also choose other effects on top of the successful action. If they miss, they are ‘Falling’, and the player must choose to allow the situation around them to get worse, at which point the Mistress gets to make a falling move, essentially pushing the flow of action against the player, or they may take action to resist the effects of bad fortune. If they have a move that can modify the result or if they are willing to spend an in game currency called Boost Chips, they may fall forward. When falling forward, the player trades damage (either damage their character sustains or damage the character deflects toward someone else) in return for choosing an effect from the missed move as if they were actually rising.

Along with these two states, there are two more extreme states that can come into play when more dice hit the table. If the die roll has three hits, then the character is Sparkling, giving them two boost chips, one to take for themselves and one to share among the other players. Along with this bonus, most Moves have a Sparkling effect you can activate in this more elevated state. On the other side of things, when at least half of your results are a 1, then you are Trash. When Trash, you cannot modify the results of the move, either by spending boost chips or by using moves.

The language describing these different states is one of my favorite things. These four states describe the position of your pilot, but they all feel inherently like value judgements. They feel voyeuristic. There are not weak states or strong states, which could describe something internal, you are rising, falling, sparkling, or trash. One imagines that these are the way spectators might describe the performance of a dancer, or an athlete. What is also interesting is that as soon as you take an action, you gain a state. Each of these states correspond to moves, that can be activated depending on this state. For instance, the Rat Bitch, my not so secret favorite of the pilots, has the ability to actually modify their results when they are trash because, as the author so perfectly says, “of course she does.” This, I think is what centers the play in Violet Core. The game design creates a narrative that, whatever you are doing, your character is affected by the idea that someone is always watching them, watching them succeed, watching them outshine others, watching them fall, and watching them become something worse than worthless. That constant self description literally affects what they are capable of. It is not just that you want to succeed, you want to succeed in such a way that you look good. And more than failure meaning you cannot accomplish what you attempt, failure makes you look bad, and if you look bad, you are bad.

We mentioned the two aspects of the game that determine the dice pool. When making a move, you use an appropriate talent and then may spend currency to modify the move further. There are ten talents, in total, six pilot talents and 4 X-10 talents. Pilot Talents represent the character as an individual and their strengths and skills. The names are very descriptive, and help to frame the sort of action expected of characters in the narrative the game creates. The X-10 moves deal with how a pilot controls and is controlled by the X-10. What is especially fun in the X-10 moves is that none of them directly point to causing violence. Synchronize, Distance, Touch, and Draw Near deal mostly with relationships of space and understanding between a pilot, their x-10, and other x-10s. I find that this set of talents, which describe the ‘how’ of a move where the move itself describes the ‘what’, creates a game where players have to actually consider what they want to accomplish. You can essentially do whatever your moves permit you to, but in considering which talents make sense to roll, the player and the Mistress have to directly consider the characters, the setting, and what the moves ultimately mean for them. If a game that ties its standard actions around combat encourages combat, and a game that ties its standard actions around skills encourages considering skills, the myriad descendants and hybrids of the original apocalypse world create games that encourage this two part consideration. What does one want to do, and how does one want to do it? Sarah has a page dedicated to this question, since ultimately the decision of what talent to use for a move is up to the player. She describes what each of the talents largely covers, and then gives two ironclad rules that must be held to in the game: First, that it must be true to the character. Second, the talent ‘Making Out’ and the move ‘Get Close’ require consent to be used.

Before we talk about the final building block of the game system, that second rule for considering talents and what it says about this game merit a little more discussion, specifically in regards to certain expectations of content in this game. Intimacy, relationships, romances and trysts, Violet Core takes such themes and situations and pushes them to centre stage. It does so not as an afterthought, and without assuming such a thing will come naturally to everybody. It lays out how to make sure that the players and their characters know what they want and where they are going. It gives ironclad rules of consent for game mechanics that invite narrative situations where things like touch, or just a certain sort of conversation or activity, are expected. It even does so for the real world around-the-table-activities. It is, in short, something that the author of the book considered carefully and it shows.

A lot, and I mean a lot, of games that came out of the Powered by the Apocalypse framework deal with relationships and intimacy. Violet core even describes its mix of Monsterhearts, Fate, and the sort of genesis media of Heaven Will Be Mine in terms of gross silly intimacy. What is important to this, your author feels like pointing out, is that this is something of a norm nowadays. In fact, there is less to be said in pointing it out for the benefit of you, dear reader, as I am sure you’re aware of this. More that it feels important to see that in being straightforward about such content, the game is setting an example that players would do well to follow. Being straightforward about expectations is important in these sorts of games. Ideas like lines and veils, as well as their limitations and further refinements of such contracts when playing games came out of knowing both the interest and pitfalls in placing intimacy specifically, and challenging content in general into role playing games. Perhaps, to tie it back to what was said in the introduction, because roleplaying games combine the ability to imagine and embody whatever we want with the need for there to be honesty and trust in the real world interactions that create them, they are in fact tools of self introspection. It is very hard, and often times very painful, to lie about if we are having a good time or a bad time. It also becomes harder and harder to ignore what we enjoy, and to consider what it springs from. One can only put on torn dresses and messed up makeup so many times ‘as a joke’. One can only describe desires to see certain people in certain relationships in their games, to cry and pine and laugh with joy about it, so many times ‘you know, as a mental exercise’.

Back to system stuff.

There are two currencies in the game, connections and boost chips. There are also crash chips, a sort of anti currency that comes when a Mistress is able to use one of their moves to steal chips when things go bad and the pilot is trash. Connections between the pilots are created at character creation, and grow when players attempt to make connections with each other. There are four levels of connection, each one modifying the dice in question. All levels of connection will give the player a certain number of connection dice, which are unique in that they ‘hit’ on 2’s as well as 4’s. This is massive. On top of this, if a player rolls a 4 on a connection die, then it counts as 2 successes. If a player also Sparkles while rolling a connection die, then the connection deepens. This affects not just the number of connection dice, but pilots who are deeply connected do more damage. There is a lot to gain from connections but a lot can be lost as well. There is a mechanic specifically when things are not working out, and a relationship is halted. When halted, a player trying to make a connection has their dice pool reduced by 1. They can still work together, but it is diminished. On the other side of it, if they are able to reconcile their differences, then they both earn a boost chip and the connection can grow again.

While connections are a sort of currency and also a sort of stat, boost chips are completely abstracted. They have no in game analogue and are essentially there for the sake of allowing players to modify rolls, requiring players to choose to do certain actions at the expense of losing something valuable, and to entice individuals down different paths. Players start each session with one boost chip and can have up to three at any given time. During play, a boost chip can be spent to activate a pilot’s connection ferocity, allowing her to deal more damage based on the status of her connections, or they can be spent to boost one of the dice in their pool . A boosted die goes from being a d4 to a d8, and hit on 4s and 6s. If a player rolls an 8, then like with a four on a connection dice, it counts as 2 successes. The math here is interesting. A connection die gets a success 1/2 the time, vs 3/8s of the time with a boosted die. A connection die counts as two successes 1/4 of the time, instead of 1/8. Connection dice are better, but a boosted die comes out of the players own pool of dice, as opposed to connection dice which come from another player. The interactions point to a certain idea, that these pilots can be very strong on their own, but are stronger together, and stronger still when they are willing to give up a part of their strength to another.

Crash Chips come about either by misfortune or by spending boost chips. When a boost chip is spent, it goes to the Mistress and becomes a crash chip. Similarly, when a pilot is trash the Mistress either takes one of their boost chips away and makes it a crash chip, or if the player has none the Mistress will get a crash chip anyway. These make injuries hurt and make actions harder. They are a reminder that pilots are dealing with very big forces with very long arms, in a very dangerous world.

Connections can become messy, in terms of the game’s numbers. Since there is no rules against multiple pilots connecting at the same time, and indeed this is promoted by the game, the book flat out says that there is an ideal number of players for the game, around three. With more, the amount of damage and success becomes a bit wild if all present are spending currencies freely and keeping the exchange between them and the Mistress going. The suggestion of just leaning into these numbers and simply giving them harder missions with more targets and more issues to deal with feels right.

Indeed, this entire game feels enthusiastic and messy. It is a game about embracing connection, being vulnerable, being hard to deal with, drowning in your own ego, and either giving yourself over to an organization that uses you or refusing to do anything for the sake of said organization even when it is actively helpful. It is a game that begins with the fact that the players are not explicitly on the same side. Sometimes they explicitly are on opposite sides. It says that is fine, and indeed when we get into dueling, the sort of crown jewel of this system, it encourages all of this even further. The vulnerability, the mess, the desire and the conflicting convictions all come to a head when the pilots, in their giant, tailor made, awe inspiring machine forms duke it out for the sake of… something. The dueling is the most exciting aspect of the game, and the mechanics it uses are novel and fun. However, they will not be described much more, at least not in this review. It is long enough.

Moreover, if anything described in this review, if any of the quirks of the ruleset, or the fun of the setting, or the satisfying resonance of both working together to create such a narrative that feels both easy to imagine but also impossible to see all the options for, intrigues you, then selling the dueling system is not necessary. Back the Kickstarter. Get the rules. Play the game with some folks. Moreover, do not assume that you already know if this game is for you or not, dear reader. It is obvious that such a thematically tight game will be deeply desirable to all who get it, but an inability to click with it so instantly should not dissuade the curious. Indeed, even the smallest bit of curiosity should be encouragement to try it. If the art intrigues, if the concept of either being a paragon of a flawed vision for a better humanity OR a damaged soul giving up relevance or glory in favor of warmth or intimacy intrigues, if a different sort of system that encourages a different sort of play intrigues, it is worth trying for the sake of that. You’ll never know what you’ll learn from trying new things, especially about yourself.

by Kiki Kwassa

Don’t miss the Kickstarter where you can get the book and help fund further stretch goals and rewards!

Tags | indie rpgs, kickstarter, rpgs